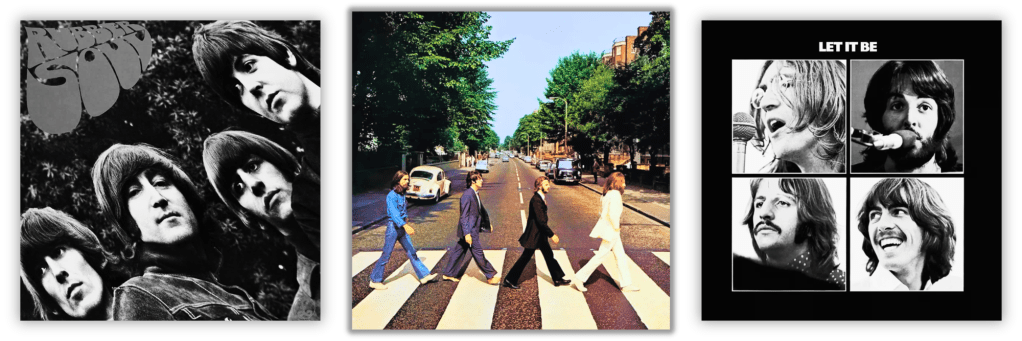

For a long time when I was younger, Rubber Soul was my favourite Beatles album. Recorded when they were in their mid-20s, it has an easy, natural optimism that I found very attractive. The Beatles were young, talented, good at what they did, and just starting to discover themselves as artists and people. There was a lot for them to be optimistic about, and it came across on record. It was an easy album to like.

In 2023, as an older man, weathered and scarred, I rediscovered Abbey Road and decided to change my mind. It was my favourite listen of that year, and I think my new favourite Beatles album, for much the same reasons that Rubber Soul is so great even though in many ways they are complete opposites of each other.

In contrast to Rubber Soul’s easy and natural optimism, the positivity in Abbey Road was a deliberate and hard fought choice. Leading up to its creation were the disastrous Let it Be sessions, and when they fell apart the vibes between the members were mostly very bad. But not all the way bad all the time. Only three weeks later the group decided to get back together again, to give it another go.

Paul McCartney said: “it was like we should put down the boxing gloves and try and just get it together and really make a very special album.” And producer George Martin said “Nobody knew for sure that it was going to be the last album – but everybody felt it was.”

The Beatles at this point were always on the verge of breaking up; they had grown into different people, and they had just been through too much. But they were clear-eyed on what the situation was, and going into Abbey Road they decided to choose joy anyways. Focusing in on what was important, the music that only they could make together, the resulting album was mature, complex, and radiated optimism. It was arguably the best of their career. Choosing positivity regardless of your challenges and just focusing on what’s really important seems to have yielded them excellent results in the face of adversity. Don’t get me wrong, Rubber Soul is still a great album, it’s just that natural optimism during the good times is less interesting than deliberate positivity during the tougher ones.

Rediscovering this album now was timely, because on many fronts 2024 was randomly not great.

The night before my daughter’s birthday, our basement flooded from the rain. Most of the floor and drywall had to be removed, we had to do waterproofing and install a sump pump. We had to find the sources of water and close them up. Some of that water came from a poorly positioned old shed, so we had to get that disposed of and get a new one. Huge cracks appeared in our driveway from the rain, so that had to get repaved. Then our dishwasher broke. And our washer and dryer were on their way out so why not replace those too.

Now that we were warmed up, things could really start to go wrong. We had an active leak from our master bathroom dripping onto an old plaster ceiling, and because the moisture was behind the bathroom tile we had to demolish the master bath and build a new one. And because old plaster has asbestos, to remove it properly you have to seal off the impacted areas and move out of the house. And once you’re doing that you’re going to do a few other things too.

While my wife was in her last trimester of pregnancy, we packed up and moved to my parents house and ended up managing over 20 contractor jobs or major deliveries just to make the house work properly again.

Somewhere in between I sprained my ankle for absolutely no reason, got COVID, got into a minor car accident with less-than-minor damages, and I found that my credit score had accidentally been merged with somebody else with a slightly similar name, which I then had to get unwound. There is no reason why Ian Lee needs that many credit cards. Also, Trump.

With chunks of my house, car, health and possibly my credit rating were in some comical state of constant disrepair, none of it ever really got to me. It kept me busy, annoyed and somewhat poorer than when I started, but I was never actually upset. Because I knew that what was important in my life was the health and love of my family. My wife and daughter are both the sources and recipients of all the positivity and optimism and joy in my life. Everything else is just stuff.

My daughter is now 4, and was born very prematurely during the pandemic, and spent her first three months of life in the hospital. Tiny and red in her incubator, the beeping machines helped her undeveloped lungs breathe and monitored her heart, which we hoped would not require a surgery. That got to me, as it should. Because these are the real problems, the ones that rightfully keep you up at night, the ones that really threaten the things that matter. Today, she is an energetic, caring, sharp and articulate junior kindergartener, and amazes me on a daily basis. One positive side effect of the traumatic start to her life is the gratitude we feel for her simply just being. It will probably last us the rest of our lives.

My wife continues to amaze me. When we first started dating we both had a feeling it’d be about that good forever, and 10 years in that seems to be coming to pass. We share the same values, want broadly the same things, and we make a strong and complementary team. She is hilarious in ways that are rare and original, and still surprises me to this day. I couldn’t have asked for a better partner in life, and I still stare at her face sometimes in admiration when I don’t think she’s looking, but she is probably looking because she sees everything somehow.

And to our new son, just born a few weeks ago. Of all the things that happened to us this year, your safe passage into the world was the one sole thing we were all hoping and praying for, especially given what happened with your big sister. Through the floods of the summer and the unplanned major renovations of the fall and winter, as long as you were growing bigger and stronger in your mother’s belly everything was going to be fine. Every other part of our lives could happily fall apart as long as you stayed whole, and I’d have gladly accepted all the house issues, car accidents and other misfortunes of day-to-day life if it meant that you were going to be okay.

He arrived a full term baby, exactly on time and as planned – a chonky 8lb 14oz, four times the birth weight of his sister. When I stare into my son’s eyes and he stares back into mine, it’s like looking through an infinity mirror into our shared past and future. I can see him through his eyes, but I also see my father reflected back at me, and his father before him who I never had the chance to meet, and then myself again, back and forth from the beginning to the end and back. It is 3am and he also needs a burp and a diaper change. I am tired and grateful.

Maybe one day I will introduce him to The Beatles or he may discover them himself, and assuming listening to albums or The Beatles will still be a thing in 2045, I’ll watch him to see which of their records he gravitates towards. Maybe it’ll be Rubber Soul like me, or maybe it’ll be Sgt Pepper like the rest of the world. Either way I’ll smile, knowing that Abbey Road is waiting for him whenever he’s ready to hear it.

Did you like what you read? Join my mailing list for other updates and to never miss a post: